One day, my overcrowded inbox delivered a particular message: an invitation to enroll in a MOOC (Massive Online Open Course) on information graphics and data visualization. This made me pause a bit, for a few reasons. First one is curiosity, of course: I’m obsessively curious, my memory is like a sponge, so anytime I bump into something new, my neurons start jiggling. This happened this time as well: I had never taken a MOOC before, and anyway #dataviz is something I’m quite interested in.

Second is this, precisely: I’m a hardcore scientist, and infographics are generally dismissed as “fancy, glossy and stupid” by a majority of my peers who hail the idea of presenting raw, dry facts which supposedly speak for themselves. Indeed, many infographics I have seen when browsing the web are not far from this pejorative definition as they are just a nicely put brag of a gifted designer but bring no insight whatsoever in the information they are supposed to present you.

Third is that I somehow got into data storytelling, or making big boring numbers relevant for the layman. I know many people — including myself! — who are not keen at all digging into the World Bank Database and reading about GDP or GNI or whatever the eggheads out there have decided to call it. This repulsion is, however, much easier to overcome when you are scientist for the mere reason that a major part of your daylight job is just this: crunching raw boring stuff to make sense of it.

How was I supposed to reconcile my somewhat innate obsession of analysis, of uncovering mechanisms and ‘reverse engineering’ even art pieces — which supposes a great sense of detail and possibly a quite rigid mindset, unwilling to give up on details — with depicting and abstracting this incredibly broad range of information into an infographic? I gave it a try or two on my own. I was not happy, either because I feared it was too heavy on facts (the mechanistic freak was too present) or because in an attempt to make it understandable, it was sloppy (the perfectionist came forward).

Then the course kicked off. And my talespinner-scientist schizophrenia got a breathing space 🙂 This sums it pretty well: “The life of a visual communicator should be one of systematic and exciting intellectual chaos.” This just sounded right to me and for me. The quote is courtesy of Alberto Cairo, our instructor, who does an amazing job introducing things in a progressive and logical fashion. I recommend you follow him on Twitter and/or read his blog as his prolific remarks are really worht the read (and funny).

Here are thus a few things I believe everyone out there should know. These seem very important to me to highlight as everyone out there is exposed to some representation of information. It is thus important for any of us to understand what nice colours and forms say — if they say anything at all, of course. Additionally, I believe that if we have more people understanding what #dataviz at large can bring us, we will all contribute to more high-quality materials and more knowledgeable society.

What Alberto Cairo teaches us revolves around the main idea that #dataviz is “a piece of functional art.” More precisely, the world is full of information — what he dubs “stuff”, or in other words, an amount of amorph material that we cannot use as is. Living beings such as are able of processing this raw useless stuff: we have brains for this (at least, some of us do…). The brain thus outputs a shape, but “the brain envisions a shape given a purpose,” emphasized Alberto.

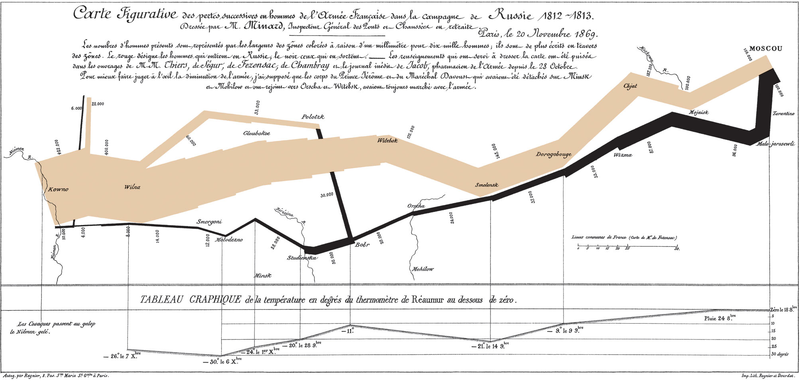

Charles Joseph Minard’s famous graph on Napoléon’s invasion of Russia showing the decreasing size of the Grande Armée as it marches to Moscow (brown line, from left to right) and back (black line, from right to left) with the size of the army equal to the width of the line. Temperature is plotted on the lower graph for the return journey (Multiply Réaumur temperatures by 1¼ to get Celsius, e.g. −30 °R = −37.5 °C). Image from Wikipedia (Public Domain)

In the 21st century, we have to deal with information doubled with complexity. If yesterday the question was how to process clay to make a statue, nowadays we have technologies such as the internetz which greatly increases the amount and complexity of information one has access to on an everyday basis. How do we make sense of complexity then?

The goal of information designers is to tame information complexity. A tool for this is a graphic. It extends our skills and capacities. An infographic thus is the wise combination of the following:

- functional as a hammer;

- multilayered as an onion;

- beautiful and true as a mathematical equation

Doing an infographic, to my relief and satisfaction, thus follows the thinking path I’m so much used to, that is:

- ask a question: what question would the readers be willing to see answered?

- choose representations: which data and charting forms suit the best? An important point is to remember that “function restricts the variety of forms that are acceptable to use for each story and set of data.”

The bottom line here is that charts, maps and diagrams all represent data that the bare eye does not (easily) see otherwise. I like this because it implicitly pinpoints to the importance of exceptions — that is, the uneven data points. What also appeases me thus far is that art thus should not prevail over analysis, that is graphics are tools, not just stuff to make your data storytelling as fancy and glossy as possible.

I’m done with the video and reading material for this first part. Now: time for exercises 🙂

Relevant reading (imho):

- The Manard’s famous map (featured above) is a part of the Wikipedia “French invasion of Russia” entry. A good one, worth reading!

- You may be interested to read more about nowadays tube maps, formalized by Henry Beck in the 1930s.

- The Guardian has an awesome Data Blog: it allows you to not only have data explained in a nice and comprehensive way but also to obtain the datasets and tell your own story out of them. The Guardian also has a ‘data journalism’ section.

- datavisualization.ch, for advanced #dataviz fans

- The Data Journalism Handbook, thus far in version 1.0 but already a fabulous resource.

- Data journalism from Stanford University

- Lastly, I’m not very familiar with this blog (yet) but it looks worth the browsing.

Very nice post. Thank you. I won’t think anymore of infographics as the fashion victims in the geek world… Ok. Just a bit less 😛